- Home

- Studs Terkel

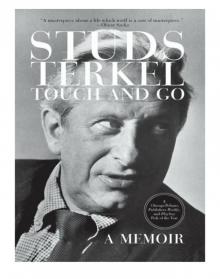

Touch and Go Page 3

Touch and Go Read online

Page 3

There was the usual ethnic slurring among the neighborhood’s youngbloods (eight, nine, ten were their ripening ages). And there was 1920, when a tripartite understanding overcame. It was the time of the troubles in Ireland; the time Yeats celebrated the birth of “a terrible beauty.” It was a time when all the kids on the block became Irish. Terence MacSwaney, Sinn Fein’s Lord Mayor of Cork, was on a prison hunger strike of which the whole world was aware. We all wore huge buttons that covered the lapels of our tight little jackets three times over: FREE TERENCE MACSWANEY. After seventy-five days of fasting while in Brixton Prison, he died of starvation and the troubles multiplied. Nonetheless, we had done our bit for Irish freedom. Had we known “Kevin Barry,” we’d have sung it out, with more fervor than the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem. There was a worldwide protest, no demonstrator more fervent and fiery than my brother, Ben, a flamboyant ten, displaying as many buttons as a cockney pearlie. No shining scholar at school, he astonished all with his eloquence: “A nation which has such citizens will never surrender.” Was this our street-talk Ben or a young William Jennings Bryan? My mother immediately touched his forehead to make certain his temperature was 98.6 though she’d settle for 102. Ben had picked up the lingo from his nonscholarly buddy, Quinton Moore, who’d had it smacked into his head by his scholarly brother, Jerry. Jerry had read the item somewhere in a Sinn Fein sheet. It was a comment of Ho Chi Minh, a young dishwasher at a London restaurant just before he latched onto the job as pastry chef for Escoffier at the Ritz of Paris.

The ones we most respected on the block were the big boys on the corner. Getting on their good side was our prime desideratum. They bore their names with a tribal pride: Irish, Dutch, Blackie, Greek. (In fact, though the two left fielders of the Giants and the Yankees, the Mueller brothers, Emil and Bob, were German, they were popularly known as “Irish” and “Dutch.” My brother Ben was a true neighborhood boy. Schooling was not his true love; his mentors and patrons were the big guys on the corner. There was little doubt that of all the kids Ben was their runaway favorite. I can still hear their requests for his throbbing rendition of “Break the News to Mother.” They tossed nickels and dimes at him, though there was nothing patronizing about the gesture. It was as though sentimental passersby were paying tribute to a street singer. He picked up enough change in that manner to occasionally take me to a Saturday feature and a Pearl White serial. The Civil War song was to Ben what “Casey at the Bat” was to DeWolf Hopper, or “Over the Rainbow” to Judy Garland.

Just break da noos to mudder

Y’know how deah I love ’er

Tell her not tuh wait fer me

F’r I’m not comin’ ho-o—me.

Now and then, Dutch or Irish or Greek would engage Ben and Quinton, the ten-year-old wonders, to box a wild round or two. Winner take all—a dime. It would usually wind up in a draw and each warrior would be a buffalo nickel richer. Neither Ben nor Quinton knew of the Marquis of Queensberry rules nor did they much care. They aimed for each other’s groin; they rabbit punched. And even pivot punched, a maneuver that was outlawed a half-century before.

Meyer was respectfully recognized as the family scholar. He was known in the neighborhood and respected by Irish, Greek, Blackie, and Dutch. It was a case of all being neighborhood boys. He had college in mind and they knew he’d become a teacher. The fact that he enjoyed and understood baseball and was a Giants fan didn’t hurt matters. There were few Yankee fans in the community, even among the Italian kids. This was in the pre-DiMaggio days and Tony Lazzeri was the only recognized name.

Bulldog was our baseball aficionado. I, not much for anything physical, merely a good listener, was his perfect audience. Thanks to him I could rattle off the million-dollar infield—George “Highpockets” Kelly; Frankie Frisch, the Fordham Flash; Davey Bancroft; and Heinie Groh, recently acquired with his bottle bat from the Cincy Reds; he was the bunting artist. John McGraw was of course our god.

Bulldog didn’t mind his block-given name because he did indeed bear a remarkable resemblance to the species. Bill Mauldin recalls his encounter with General George Patton and his most dear companion, his bulldog. Bill, a kid combat correspondent in World War II, was a cartoonist; his protagonists being Willie and Joe, a couple of footsloggers. On occasion, Mauldin had some masterpieces ribbing the pompous brass. Who was better meat than Patton? One day, the general, furious, demands the presence of Mauldin. The kid peeks into the office and recalls: There was Patton, in one chair, glaring; there was his bulldog in the other, usually fearsome. “I looked into two pair of the meanest eyes I’d ever seen in my life.”

No, my baseball mentor was a progressive kid, more of the John Dewey type. When I hesitated in guessing the name of a baseball manager, he’d break a branch off a tree. “Branch Rickey,” I’d exclaim.

What I best remembered as we left New York for Chicago was a play Bulldog told me about. It was during the Cleveland Indians–Brooklyn Dodgers World Series of 1920. A second baseman of the Indians pulled off an unassisted triple play. It was the only time ever it occurred in a World Series. Bill Wambsganss was his name. Every fan called him Wamby.

There was one more celebrated name I remember from our journey to Chicago. How could I disremember Professor Émile Coué, who made the front page for months? His credo for good health: Simply think and repeat, “Every day in every way, I’m feeling better and better.”

As I recall, Professor Coué had a well-trimmed beard and a perpetual smile. Fifty years later, I ran into his kindred spirit, W. Clement Stone. He headed what was probably the country’s most successful insurance outfit, the Combined Insurance Company. He owned the building plus just about everything else within reach. He contributed more to Richard Nixon’s “Four More Years” campaign than any other American.

Behind a mahogany desk, huge, sits the ebullient CEO. He is little, wears a pencil-thin mustache and a wide bow tie. He is in Fortune magazine as one of America’s new centi-millionaires. The corridors are enriched with familiar, beloved waltz and foxtrot tunes. He immediately presents me with several books: Success Through a Positive Mental Attitude; The Success System That Never Fails ; and Think and Grow Rich. He refers to the last.

That’s the greatest book that came out of the Depression, by Napoleon Hill. That motivated more people to success than any book you could read by a living author.

As for me, first of all I thank God for my blessings. Then I’d use a very simple prayer: Please God, help me sell. Please God, help me sell. Please God, help me sell. I say it at least four times each morning, facing the mirror. This did many things, the mystic power of prayer; it got me keyed up. I threw all the energy I had into it. Immediately, I’d relax and go to a movie—and then, r-r-r-ight.

“So you recall any of those sad moments during those hard days?” I asked.

“I don’t believe in sadness. I believe if you have a problem it is good. Maybe I had a poor day. I’d rest, go to movie. The next day would be a rrrrecorrrrrrd day.” He and Professor Coué were true kindred spirits. Kindred spirits. I like that. Rrrrright. And so with Mr. Stone’s kindred spirit and the miracle of Wamby’s triple play in mind, I was on my way Chicago, The City of I Will. (I’d neither heart nor mind to ask Nelson Algren’s question: “What if I can’t?”)

2

Bound for Glory4

Bound for Glory (1920)

Away up in the northward,

Right on the borderline,

A great commercial city,

Chicago, you will find.

Her men are all like Abelard,

Her women like Heloise [rhymes with “noise”]—

All honest, virtuous people,

For they live in Elanoy.

So move your family westward,

Bring all your girls and boys,

And rise to wealth and honor

In the state of Elanoy.

—A nineteenth-century folk song

When Abe Lincoln came out of the wilderness and loped off

with the Republican nomination on that memorable May day, 1860, the Wigwam had been resonant with whispers. Behind cupped hands, lips imperceptibly moved: We just give Si Cameron Treasury, they give us Pennsylvania, Abe’s got it wrapped up. OK wit’chu? A wink. A nod. Done. It was a classic deal, Chicago style.

As ten thousand spectators roared on cue, Seward didn’t know what hit him. His delegates had badges but no seats. Who you? Dis seat’s mine. Possession’s nine-tent’s a da law, ain’t it?

Proud Seward, the overwhelming favorite, was a New Yorker who had assumed that civilization ended west of the Hudson. He knew nothing of the young city’s spirit of I Will.

When, in 1920, Warren Gamaliel Harding was similarly touched by Destiny, there had been no such whisperings in the Coliseum. Just desultory summer mumblings (it was an unseasonably hot June: 100 degrees outside, 110 inside; bamboo fans of little use): Lowden, Wood, Johnson. Wood, Johnson, Lowden. Johnson, Lowden, Wood. Three frontrunners and not a one catching fire. How long can this go on? Four ballots are enough. C’mon, it’s too hot for a deadlock. Shall we pick straws?

But this wasn’t just any conversation city. This was Chicago. Never mind the oratory. Yeah, yeah, we know about the Coliseum where, in 1896, the cry was Bryan, Bryan, Bryan as the Boy Orator thundered eloquently of crowns of thorns and crosses of gold. Nah, nah, let’s settle this Chicago style.

A hotel room not far away.

The Blackstone, so often graced by Caruso and Galli-Curci during our city’s lush opera season, was on this occasion beyond grace. Nah, nah, it’s too hot. Maybe the Ohio Gang ran things that day, but with blowing curlicues heavenward from H. Upmann cigars in the smoke-filled room, the deal—Harding, OK?—was strictly My Kind of Town, Chicago Is.

AS FOR MY CITY, Chicago, yet, along came Jane Addams. Was it in 1889 that she founded Hull House? The lady was out of her depth, they said. Imagine. Trying to change a neighborhood of immigrants, scared and lost, where every other joint was a saloon and every street a cesspool. And there was John Powers, alderman of the Nineteenth Ward, running the turf in the fashion of his First Ward colleagues, Bathhouse John and Hinky Dink. Johnny Da Pow, the Italian immigrants called him. He was the Pooh-Bah, the high muckety-muck, the ultimate clout. Everything had to be cleared through Da Pow. Still, this lady with the curved spine, but a spine nonetheless, stuck it out. And something happened.

She told young Jessie Binford: Everything grows from the bottom up. This place belongs to everybody, not just Johnny Da Pow. And downtown. No, she told Jessie, I have no blueprint. We learn from life itself.

So many years later, years of small triumphs and large losses, Jessie Binford, ninety, is seated in a small Blackstone Hotel room. The Blackstone again, for God’s sake? It isn’t a smoke-filled room this time. My cigar, still wrapped in cellophane, is deep in my pocket. It’s an H. Upmann—would you believe it? The old woman, looking not unlike Whistler’s mother, is weary and in despair. The wrecking ball had just yesterday done away with Hull House and most of the neighborhood. Even the beloved elm beneath her window had been uprooted and removed.

The boys downtown tried to buy off Jessie Binford. You can live at the Blackstone as our guest for the rest of your life, they told her. Anything to keep her quiet. She and a young neighborhood housewife, Florence Scala, were making a big deal out of this. Sshhh. But they wouldn’t shush, these two.

THESE TWO.

Florence Scala, first-generation Italian-American. Her father, a tailor, was a romantic from Tuscany. He was a lover of opera, of course, especially Caruso records, even the scratchy ones. He had astronomy fever, too, though his longing to visit the Grand Canyon transcended his yen to visit the moon. He was to make neither voyage. The neighborhood was his world and that was enough.

For Florence, her father’s daughter, the neighborhood reflected the universe, with its multicolors, its varied immigrant life, its cir-cumambient passions.

Jessie Binford, of early Quaker-American stock. Her father, a merchant, trudging from Ohio to Iowa in the mid–nineteenth century, found what he was looking for. The house he built in 1874 “still stands as fundamentally strong as the day it was built,” his daughter observed. At the turn of the century, she found what she was looking for: a mission, Hull House, and a place, Harrison-Halsted. She found the neighborhood.

For Florence Scala and Jessie Binford, Harrison-Halsted was Blake’s little grain of sand.

They passed each other on early-morning strolls along these streets, not yet mean. They came to know each other and value each other, as they clasped hands to save these streets. They lost, of course. Betrayed right down the line. By our city’s Most Respectable.

“I’m talking about the boards of trustees, the people who control the money. Downtown bankers, factory owners, architects, people in the stock market.” Florence speaks softly, and that, if anything, accentuates the bitterness.

The jet set, too. The young people, grandchildren of the old-timers on the board, who were not like elders, if you know what I mean. They were not with us. There were also some very good people, those from the old days. But they didn’t count any more.

This new crowd, these new tough kind of board members, who didn’t mind being on the board for the prestige it gave them, dominated. These were the people closely aligned to the city government, in real estate and planning. And some very fine old Chicago families.

As Florence describes the antecedents of today’s yuppies, she laughs ever so gently. “The nicest people in Chicago.”

MISS BINFORD is leaving Chicago forever. She had come to Hull House in 1906. She is going home to die. Marshalltown, Iowa. The town her father helped found.

The blue of her eyes is dimmed through her spectacles. Her passion, undimmed. “Miss Addams understood why each person had become what he was. She didn’t condemn because she understood what life does to people, to those of us who have everything and those of us who have nothing.” It’s been a rough day and her words, clearly offered, become somewhat slurry now. “Today we’re getting further and further away from this eternal foundation on which community life must rest. I feel most sorry for our young people that are growing up at this time . . .” It’s dusk and time to let her go. I press the STOP button of my Uher.

Our double-vision, double-standard, double-value, and double-cross have been patent ever since—at least, ever since the earliest of our city fathers took the Potawatomis for all they had. Poetically, these dispossessed natives dubbed this piece of turf “Chikagou.” Some say it is Indian lingo for “City of the Wild Onion;” some say it really means “City of the Big Smell.” “Big” is certainly the operative word around these parts.

Nelson Algren’s classic Chicago: City on the Make is the late poet’s single-hearted vision of his town’s doubleness. “Chicago . . . forever keeps two faces, one for winners and one for losers; one for hustlers and one for squares . . . One face for Go-Getters and one for Go-Get-It-Yourselfers. One for poets and one for promoters . . . One for early risers, one for evening hiders.”

It is the city of Jane Addams, settlement worker, and Al Capone, entrepreneur; of Clarence Darrow, lawyer, and Julius Hoffman, judge; of Louis Sullivan, architect, and Sam Insull, magnate; of John Altgeld, governor, and Paddy Bauler, alderman. (Paddy’s the one who some years ago observed, “Chicago ain’t ready for reform.” It is echoed in our day by other, less paunchy aldermen.)

It is still the arena of those who dream of the City of Man and those who envision a City of Things. The battle appears to be forever joined. The armies, ignorant and enlightened, clash by day as well as by night. Chicago is America’s dream, writ large. And flamboyantly.

PARADOX: Today’s council members opposing the younger Mayor Daley are more diffuse, less cohesive, of all color, affording the son of the old Buddha more power than his old man had.

It has—as they used to whisper of the town’s fast women—a reputation.

Elsewhere in the world, anywhere, name the city, name the coun

try, Chicago evokes one image above all others. Sure, architects and those interested in such matters mention Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Mies van der Rohe. Hardly anyone in his right mind questions this city as the architectural Athens. Others, literary critics among them, mention Dreiser, Norris, Lardner, Algren, Farrell, Bellow, and the other Wright, Richard. Sure, Mencken did say something to the effect that there is no American literature worth mentioning that didn’t come out of the palatinate that is Chicago. Of course, a special kind of jazz and a blues, acoustic rural and electrified urban, have been called “Chicago style.” All this is indubitably true.

Still others, for whom history has stood still since the Democratic convention of 1968, murmur: Mayor Daley. (As Chicago’s most perceptive chronicler, Mike Royko, pointed out, the name has become the eponym for “city chieftain”; thus, it is often one word, “mare-daley.”) The tone, in distant quarters as well as here, is usually one of awe; you may interpret it any way you please. “Who’s the mare-daley of your town?”

Hog Butcher for the World, Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat, Player with Railroads and the Nation’s Freight Handler; Stormy, husky, brawling, City of the Big Shoulders . . .

Carl Sandburg, the white-haired old Swede with the wild cowlick, drawled out that brag in 1914. Today, he is regarded in more soft-spoken quarters as an old gaffer, out of fashion, more attuned to the street corner than the class in American studies. Unfortunately, there is some truth to the charge that his dug-out-of-the-mud city, sprung-out-of-the-fire-of-1871 Chicago, is no longer what it was when the Swede sang that song. It is no longer the slaughterhouse of the hang-from-the-hoof hogs. The stockyards have gone to feedlots in, say, Clovis, New Mexico, or Greeley, Colorado, or Lo-gansport, Indiana. It is no longer the railroad center, when there were at least seven awesome depots where a thousand passenger trains refueled themselves each day; and it is no longer, since the Great Depression of the 1930s, the stacker of wheat.

Will the Circle Be Unbroken?

Will the Circle Be Unbroken? Hard Times

Hard Times Working

Working Touch and Go

Touch and Go P.S.

P.S. The Studs Terkel Reader_My American Century

The Studs Terkel Reader_My American Century